A brief history of communication theory.

For thousands of years, people have been asking the same question: what is communication?

Communication is a foundational part of human life. So, it's not surprising that we've been discussing its importance and impact on society for literally thousands of years.

I'm no different. I have an almost devout reverence for the subject. I'm always researching the best practices and principles as well as studying the methods and mediums of great communication.

Recently, I've been reading about the popular academic theories and histories of the field. My research has been by no means exhaustive; like I mentioned, we've been discussing communication for as long as we've been communicating.

However, by going back and exploring its academic life at the intersection of philosophy, mathematics, and sociology, I feel I've gained a greater perspective on what communication actually is.

I plan on talking about my personal view in another post - so follow me on Twitter if you want to see when I press publish. But for now, I just want to share a few of these theories with you.

My hope is that, by showing how these views of communication have evolved over time, I can inspire you to question your own assumptions about the discipline and see how swapping lenses can make you a better creator, leader, and professional.

We begin our adventure over 2000 years ago - in ancient Greece.

The rhetorical view of communication.

Greco-Roman philosophers like Aristotle were especially obsessed with rhetoric - the process of persuasion. This is a practice centered around discourse and debate, shaping an audience's understanding of a subject to yield a desired effect.

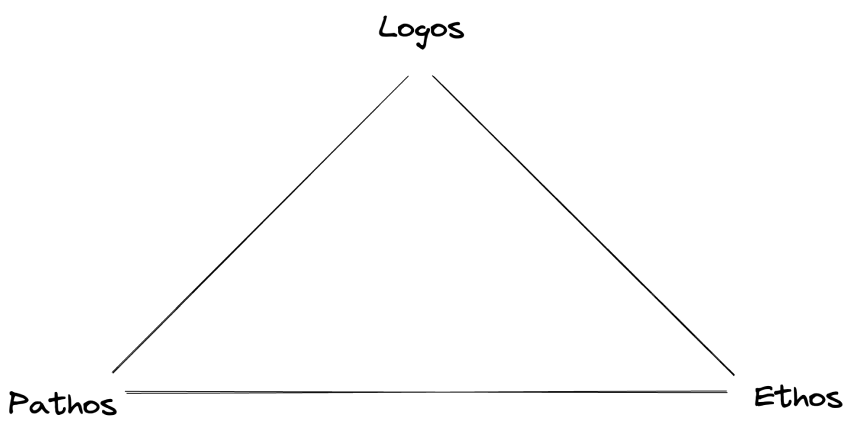

The rhetorical view of communication focuses on the relationship between a speaker and an audience. This was the foundational theory of communication in the western world, and artifacts of this era like Aristotle's Rhetorical Triangle are still taught today in schools of philosophy and film.

The Rhetorical Triangle has 3 vertices: logos, pathos, and ethos.

Logos is the actual symbols and ways we represent our ideas. Our choices of medium, style, color, type and length are all represented by logos. And yes, this is where the word logo comes from in design.

Pathos is the hearts and minds, emotions and values of our audience. Our use of story, character, and empathy all exist as part of pathos, our method for relating with others. The popular phrase, "Know your audience" likely dates back just as far as Socrates', "Know thyself".

Ethos represents us. Our voice, personality and credibility are our ethos, our ethic. It is our unique internal way of viewing the world.

As a communicator, I still find timeless wisdom in the concepts of logos, pathos, and ethos. Which is probably why this classical view of communication was the predominant view of the practice through the industrial revolution.

But that would change when two scientists at Bell Labs gave us...

The informational view of communication.

Prior to 1920, communication was largely informal. Communication theory was based in fields of art and philosophy, and scientists saw studying its principles and approaches as debating syntactic sugar rather than something of substance.

However, after seeing the immense impact communications technologies had in the first and second world wars - there was a great interest in studying communication from a mathematical and engineering perspective.

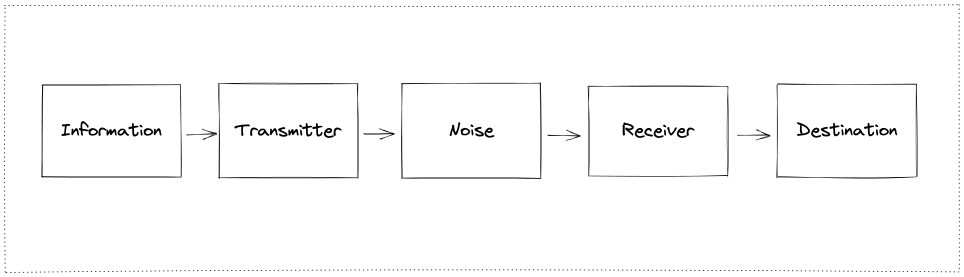

In 1949, Claude E. Shannon and Warren Weaver, two researchers at Bell Laboratories, published a paper comparing human communication to technologies like the radio and telegraph. These models were mechanistic and focused on getting a message from "an information source...to a destination with a minimum of distortions and errors".

As you can see, the model is relatively simple. Information moves in a straight line from one person (a transmitter) to another (a receiver) while passing through a source of "noise" that distorts its meaning. And although it's highly simplistic and void of all social nuance (it was written by mathematicians after all), this theory spread like lightening.

At the time, the United States was experiencing an economic and intellectual boom moving from the post war era into the space race. Companies were getting larger, the television was revolutionizing the press and media, and all of the nation's political, military, and business leaders were becoming obsessed with technology, speed, and scale.

So it's obvious why - when they inevitably experienced issues with communication - they gravitated toward a theory that aligned with their predominant cultural values and gave them a simple solution: "Increase speed - decrease noise."

And to this day, this theory of communication has dominated the zeitgeist. But as the 21st century and the "information age" has developed, we've seen the flaws in this informational industrial way of thinking about communication.

We've done nearly all we can to "increase speed". The internet enables us to send messages to multiple parties at the speed of light. And yet, business leaders still complain about the "communication breakdowns" that existed in the 1950s.

And we've learned that "decreasing noise" is exceptionally difficult. Because unlike machines, humans don't operate in a consistent, controlled system. Our "noise" isn't an external source like a rogue electrical wire. Our "noise" is a consequence of life as a social species.

Which is why, in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, the field of communication slowly and quietly emigrated out of mathematics and found a new home in sociology; where researchers wanted to study communication in context...

The contextual view of communication.

Human communication is complicated. We can never say exactly what we mean or mean exactly what we say. That's because we must manipulate our meaning to move through the membranes and mediums that make up our social context.

And researchers felt that the purely informational view of communication was insufficient for analyzing this behavior. Within the framework, there are no defined ways of discussing how the relationship between two parties influences their interactions; things like values, knowledge, language, nonverbal cues, motives, attention, attitude, beliefs, etc.

So, in an attempt to make this relationship a first-class component of the model, a variety of researchers came up with the contextual view of communication.

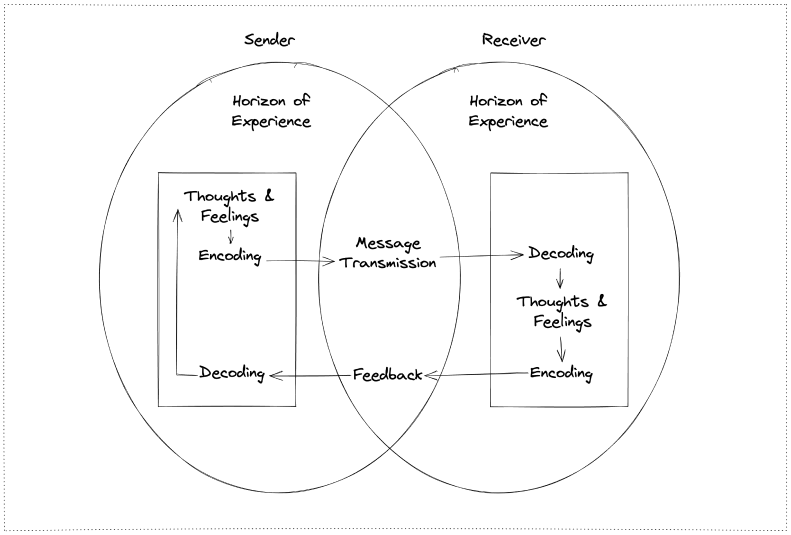

In a way, this theory combines the cold, mechanical aspects of the informational view of communication with the abstract, esoteric aspects of Aristotle's Rhetorical Triangle. There are two key differences with this approach.

The first is that this model shows communication as a continuous cycle. There is a feedback loop created between sender and receiver that represents the ways we adapt our strategy of communication based on our perception of the receiver's response to our message.

The second is the "Noise" component from the informational model has been explicitly spelled out. Each sender and receiver is defined with their own "Horizon of Experience". This is the collection of knowledge, beliefs, habits, relationships, etc. that gives each of us our unique perspective (our ethos/pathos). The intersection of those two horizons - that common ground between two parties - is where the message transfer occurs.

Also of note, after information is decoded but before being encoded, it passes through the sender or receiver's "Thoughts and Feelings". This symbolizes how our emotional state creates a bias towards certain information that directly impacts our communication.

Armed with this more robust model, researchers began to wonder how patterns of communication related to the social relationships that form our "Horizon of Experience". They began to deeply explore how social connections change the ways we communicate. This area of research is known today as...

Discourse analysis.

The field of discourse analysis is very vast. In my reading, it led me down a looonnnnggg rabbit hole (that I'm still in) into the world of epistemology - the academic study of knowledge.

However, one of the relevant ideas related to communication theory is that the social influence of communication is holistic. Our relationships don't just affect our communication; our communication creates our relationships.

Intuitively, we know this to be true. When we converse with friends, family, coworkers and strangers, we develop our connections with them. Over time, those relationships grow, change, and adapt based on those conversations and shared experiences.

However, what we don't normally think about is how our greater social lives are a web of these connections. Our "Horizon of Experience" changes with every moment of formal and informal communication in our lives. And in that moment of change, the intersection we have with everyone changes.

Skeptical? Good. Here are some questions to ponder:

How does your relationship with your spouse affect your relationship with a coworker? How does your relationship with your coworker affect your relationship with your sibling? How does your relationship with your sibling affect their relationship with a friend? How do your relationships affect a new relationship with a stranger? How do your relationships affect someone you will never meet?

When we communicate with each other, we aren't solely constructing an individual relationship - we're constructing and changing the interconnected web of society. Each one of our interactions influences (in some way) everyone's relationships with each other.

To put it simply: we're all connected. Every interaction constitutes everything we are. Which leads us to the most modern view of communication...

The constitutive view of communication.

This is where things get wild. Rather than analyzing how communication happens, the constitutive view focuses on what communication creates. This video by Matthew Koschmann, a communications professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, explains this distinction really well.

Essentially, this socially constructivist idea of communication sees our entire society as a product of the process.

Governments, businesses, organizational hierarchies, friend groups - these things aren't manifested by anything physical, tangible, or timeless. They are only meaningful because the members of these social structures believe that they are. And they only find their way to that collective, shared belief through communication.

Communication isn't solely about transferring information from one party to another. It is about managing shared knowledge. Communication cultivates a shared reality where we work and operate as a collective.

Communication is a process of capturing, connecting, and curating knowledge in order to create something meaningful. This fundamental change in the way we reason about and understand communication proves the adage...

"Communication is key".

Communication is the way we create the world around us. As an imaginative, curious, and social species, it is at the heart of everything we do. I hope by seeing these theories throughout time, you can see why I and so many others have been obsessed with understanding the power and process of communication.

By becoming better communicators, we're able to wield this powerful tool to shape our ideas and turn them into reality. Being a great communicator makes us better at our chosen creative craft. An entrepreneur, engineer, manager, writer, baker, filmmaker, or parent is simply just a communicator messaging in a medium.

I'll be expanding on that idea in my next post: Everything is communication.

Parting thoughts

I'd love to hear whether these theories have changed the way you view communication or sparked you to reflect on your own practice.

Are you focusing too much on tools and techniques for transferring information? Do you have a great system for collective knowledge management? Let me know your thoughts on Twitter!

Until next time.